When Monsters Cry and Turntables Scream: El Océano al Final del Camino

What drew me to Neil Gaiman's The Ocean at the End of the Lane was the ambiguity at its heart. Is this magical world real, or is it how a child processes his father's grief, his family's collapse, the arrival of a woman who becomes monstrous in his imagination? The book never answers that question definitively, and neither could we. That ambiguity became the production's organizing principle - we would stage the fantastic world as if it were absolutely real, never winking at the audience, never letting them off the hook by confirming it was "just" imagination.

The story deals with family abuse and childhood trauma through the lens of fantasy. My approach to staging it was to amplify everything - make it bigger, bolder, more dramatic than realism would allow. I told the actors from the first rehearsal: we're not being subtle here. The abuse has to feel enormous because that's how it feels to a child. When you're small and powerless, every adult conflict becomes mythological in scale. The monsters had to make emotional sense, which meant the real-world horror needed to match their fantastical size.

Juan Fe Arrieta being attached by an evil puppet on stage.

Grounded, Fast, Traumatic

I’m always inclined to strip away sophistication in favor of directness. The script needed to be in plain Spanish, tactile and immediate. This show wasn't for theatre people - it was for everyone. The poetry in Gaiman's prose translated not through flowery language but through rhythm and movement. The fluidity of scene changes, the forward momentum - that became our poetic language.

Rhythm was everything. When your life is falling apart, time distorts. Everything moves too fast to process. You can't catch up with the chaos. That's what our turntable gave us - a world in constant motion where the ground beneath you keeps shifting before you can orient yourself. Each transition happened quickly, sometimes violently, because that's how trauma works. You don't get time to adjust.

We structured the staging thematically rather than just chronologically. The turntable allowed us to layer time and space - a scene playing out in the present while the past was being constructed behind it, then the whole world would rotate and suddenly you're looking at memory and present simultaneously. That spatial relationship between what's visible and what's being built in darkness became a metaphor for how memory functions.

Migue leading our cast during technical rehearsals on top of our newly minted turntable.

Puppetry as Emotional Language

Sara Sol, our puppet master, and I started the puppet work months before we had actual puppets. We used socks. We used our hands. The question was always: how do you make something without a face convey profound emotion? The answer is in the micro-movements - a slight tilt, a hesitation, the speed of a gesture. We practiced these principles on the smallest scale so that when we scaled up to six-person creatures made of foam, ripped cloth, garbage bags, and PVC pipe, the performers already understood the grammar.

The monster puppet required six operators moving as one organism. We began rehearsing by holding hands, taking synchronized steps, counting out choreography to music while the puppet was still being constructed. When it finally arrived in the rehearsal room, everything we'd practiced suddenly had weight and presence. The learning curve was steep - those first rehearsals moved at a really, really slow pace - but the process taught us that puppet work is fundamentally about trust. Six people breathing together, thinking together, becoming something larger.

The emotional range Sara built into these creatures was remarkable. A monster made of garbage had to convey rage, confusion, and in certain moments, vulnerability. That's not about the construction materials - it's about understanding that emotion lives in gesture, in the quality of movement, in negative space. When that six-person creature paused, when it pulled back slightly before advancing, we all felt fear. Not because of what it looked like, but because of how it conquered the space.

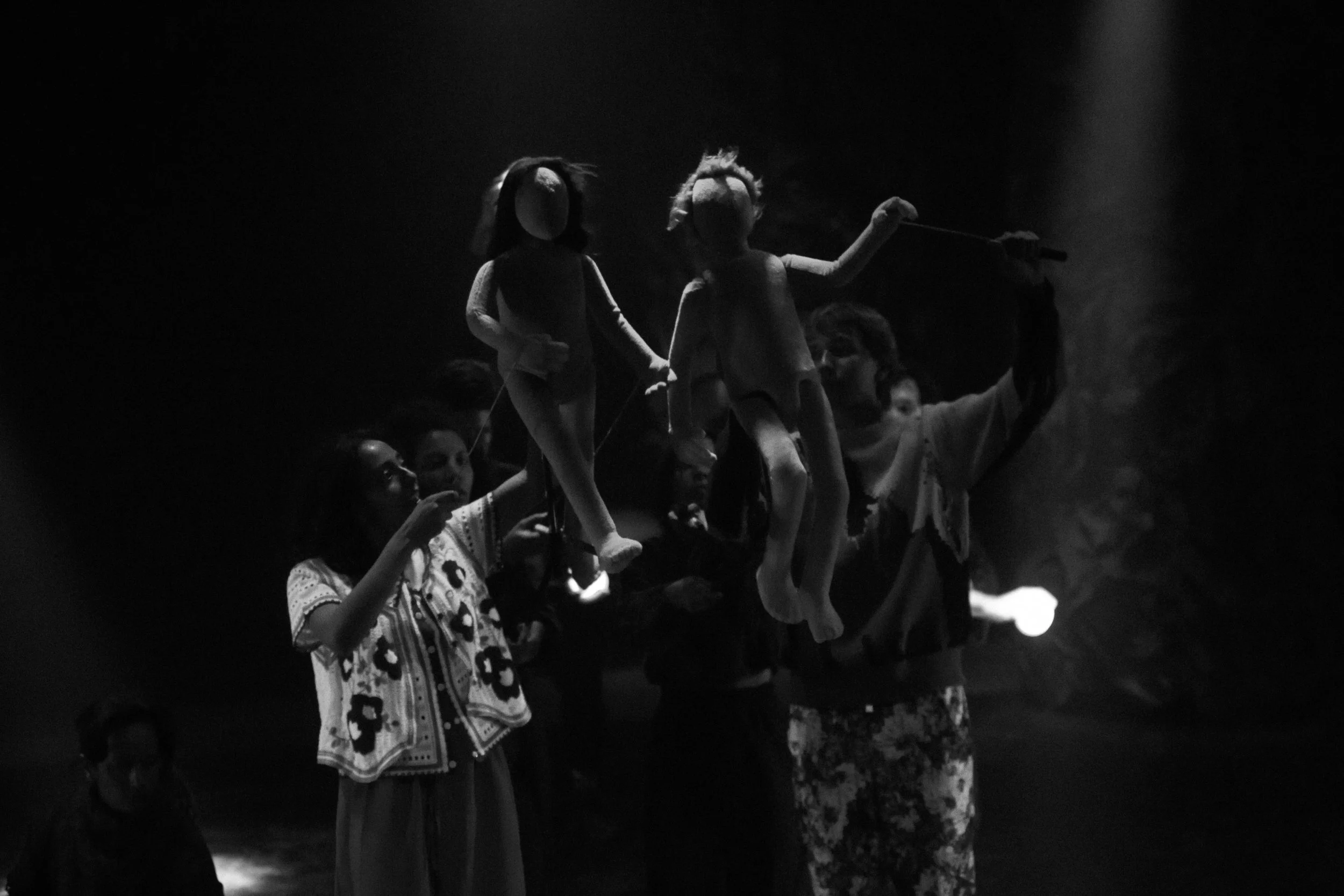

Juan Fe Arrieta and Marcela Merino rehearsing with the miniature version of their characters.

Rotating the Impossible

We'd used this same turntable before on Wendy & Peter Pan and Frankenstein, but those productions taught us what not to do. The original mechanism required too much height - the motors, the support structure, everything sat too high off the ground. In a black box theatre where every centimeter of vertical space matters, that was unacceptable. We had to engineer something that would sit lower while supporting significantly more weight.

The solution came from an unlikely source: an old truck motor and wheel. We retrofitted it with a wheel that made contact with the turntable's edge, creating just enough grip to spin the platform without the resistance that would wear out the motor. The weight distribution problem was more complex. We installed roughly twenty small wheels underneath the structure, but once the platform started rotating, you couldn't see where those wheels were positioned.

This created an immensely difficult challenge for the actors. They had to track their blocking, maintain their emotional truth in the scene, manage complex puppet choreography, and simultaneously remember which parts of the spinning floor could support weight and which couldn't. We developed strict rules about stepping zones, but enforcing those rules while maintaining the illusion of spontaneous action required extraordinary spatial awareness from the entire cast.

And…. the turntable kept dying on us. The wheels couldn't handle the entire cast constantly jumping on and off while hauling scenery. Mid-performance, you'd hear this grinding scream from underneath - parts breaking in a space you literally cannot access without stopping the show. So we'd keep going and redesign the blocking every week to ease the stress on the mechanism.

You learn to work around the impossible pretty quickly when there's an audience watching.

The turntable being installed.

Light as Architecture

The lighting design for this show required rethinking how we use light in space. Traditional overhead lighting wouldn't work for what we needed - we wanted to make the puppeteers invisible while keeping the puppets hypervisible. The solution was positioning fixtures in the wings on both sides of the stage, creating vertical walls of light that blocked the audience's view of everything behind them while illuminating only what we wanted seen.

These "light walls" allowed us to transform depth dynamically. A scene could play out on the turntable's front edge while the cast set up the next environment behind the curtain in darkness. When the platform rotated, you'd suddenly see what had been constructed - not gradually revealed, but appearing fully formed.

The glow-in-the-dark sequence was pure theatrical sleight of hand. We'd painted certain puppets and set pieces with luminescent paint and hidden it throughout the space from the opening. When the two children swim through the magical ocean, we cut all conventional light and switched to blacklight. The entire world bloomed into impossible colors.

Transitions became their own emotional language. We synchronized lighting shifts with sound - the rustle of leaves, bird calls, wind - so that lights would pulse and flicker like breath. The turntable would spin, the lights would cascade, and you'd be in a completely different emotional space before you consciously registered the change.

Our two puppets floating in the ocean.

The Challenge of Freshness

Aside from Oscar Guardado, Elizabeth Valdez and Gabri Rivera, everyone else was new to our company. This was deliberate. After working with the same core ensemble for three or four years, we needed different instincts in the room. A new cast member changes the family dynamic entirely - brings different questions, solves problems through unfamiliar methods, challenges assumptions you've stopped examining.

The rehearsal process took six weeks. We started with movement and puppetry workshops before touching the script. Table reads and blocking came later, once everyone understood the physical vocabulary we were building.

Our cast and crew.

Fantastic Answers

This production was about rhythm and relentlessness. About how trauma moves faster than your ability to process it. About the stories children tell themselves to survive what adults do to each other. About the thin membrane between imagination and reality, and whether that distinction even matters when you're small and frightened and the world feels hostile.

We staged the fantastic as real because that's what the story required. The audience had to decide for themselves: is this child experiencing magic, or is this how he's processing horror? We never answered that question. We couldn't. The ambiguity is the point.

More stories soon.

Our production was photographed by René Figueroa: